In addition to the federal tax rules, every State in the US is sovereign to adopt and administer its own tax rules. Out of the 50 US states, only 7 are income tax-free states. Florida, Nevada, Alaska, Texas, Wyoming, Washington, South Dakota. California is the highest-rate state with a whopping 13.3% rate, New York has 8.9% (and additional 3.9% for individual living in New York City.

In general, the underlying fundamental of the states tax rules is quite similar – you pay tax on your worldwide income to your state of residency (WE WILL HAVE A POST ON RESIDENCY), and you pay tax on your income that is earned in the source state, irrespective of your residency status in that state.

So for example, if you reside in New Jersey and worked in New York for certain number of days, you are taxed in New York on your income earned there, and you are also taxed in New Jersey on the same income (and all of your other income), because you reside in New Jersey. To avoid paying tax twice on the same income, states adopt a tax credit system in which your residency state allows you as a credit taxes paid at the source state.

Many states have agreements with other states pursuant to which the source state forgoes its taxing rights as a source state, and transfers the taxing right to the residency state. These are called reciprocity agreements. Many states have not entered into such agreements, for example, New Jersey. New York and Connecticut, do not have reciprocity agreements among them, although the geographic proximity. Therefore, taxpayers are often required to comply with more than one state’s tax laws.

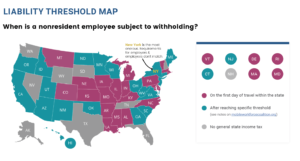

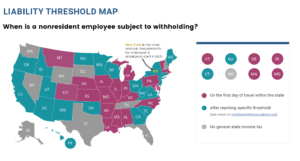

To ease on the administrative burden, many states adopted rules to provide for a de-minimis threshold, for light travelers or to immaterial income earned in such state. Imagine your job requires you to travel often and to many states and that you crossed the de-minimis threshold in several of the states you traveled to? Consequently, you may be required to file a tax return and pay tax in more than one states. Now imagine that you didn’t know about your filing requirement. This can be expensive, and unpleasant.

Employee –

Imposition of penalties, interest and addition to tax.

Employees are required to file tax returns in every state in which they earned income (or to which their income is allocated). However, most states exempt you from filing tax returns, if the allocable income to such state is below the state’s minimum taxable income (mostly determined by the state’s personal exemption amount). Failure to file tax returns may result in i

Employer –

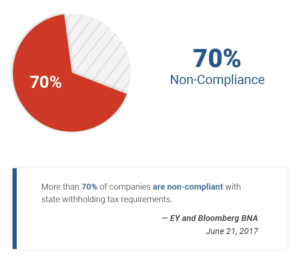

Employers are also required to comply with state tax rules that apply to employee compensation. Employees are required to withhold tax from the allocable portion of the employe’s compensation to each state the employee had worked into the extent the employee’s presence in such state resulted in crossing the de-minimis threshold. The consequences of failure to properly withhold and pay taxes to the relevant states may have a significant effect on the employer. There are interest and penalties associated with under withholding, there is a risk of state tax authorities audit, and non-curable double tax. Importantly, a failure to comply with state withholding tax requirements can have a major effect on the company’s ability to raise funds, to enter into a successful M&A, to undergo IPO, and to maximize valuation.

De Minimis

De Minimis